People use statistics as a drunken man uses lamp-posts… for support rather than illumination.

– Andrew Lang (1844-1912), Scottish poet, anthropologist and literary critic

We didn’t want to talk about Covid again, but it’s inevitable to think about it, especially now that vaccinations are reaching the wider population and the novax movement becomes louder and louder. The reasons behind fear are often not objective , but I admit that the whole debate started to interest me when I read that the highest cases of death which had been associated with the AstraZeneca vaccination occurred in women under sixty. Feeling dragged in, I decided to pull out some numbers to understand more. Is the AstraZeneca vaccine really more dangerous than other vaccines? And how dangerous is it?

Numbers,

Vaccines and Gambling

with the contribution of Stefano Lazzari

When one feels overwhelmed by other people’s opinion, it is quite reassuring to anchor oneself to the cold rationality of numbers (the tarot cards of the modern era). Once we understand the numbers, each of us can decide what to do with them. Personally, I prefer a Yoda-like approach (you either believe it or you don’t, you can’t half-believe it), but I understand that the human mind is such that today we believe numbers because it suits us and tomorrow we believe in black cats and fortune tellers for the same reason. A Macedonian colleague of mine – a physicist and builder of fine mass spectrometers destined for the Venusian atmosphere – would , if he dropped salt, throw a pinch over his shoulder and spit on the ground to his left (to chase away the devil). It is a paradox but not a contradiction, that science and superstition can coexist peacefully in each of us.

The numbers we are about to present have high error bars, due to the fact that they are fresh, they are not broken down by gender or age group, they compare different types of thrombosis, and do not take into account personal diseases and conditions. This is a way of saying that they should be taken with a modicum of skepticism, “with a pinch of salt” if you like, and should in no way be substituted for the advice of your primary care physician. That said, a high error bar doesn’t mean that the data can’t give us some valuable insights.

Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca vaccines, which have been withdrawn and/or temporarily suspended in some nations, have reported an incidence of post-vaccination blood clots of 0.0001 and 0.0004%, respectively (the fatalities caused by these clots are lower). This means that blood clots using AstraZeneca occur in about 4 out every 1 million vaccinations, this recorded over a time since vaccination started. Data for the birth control pill indicates that the risk is about 1100 thrombosis cases in a million per year, which means that taking the pill is two hundred and fifty times riskier, in terms of developing blood clots, than having the vaccine (the risk for pill-related thrombosis is does not increase with either consumption or time: like with the vaccine, starts after taking the first dose and it manifests within the first few months).

A report in The Guardian Australia is against comparing the clotting risk associated with the vaccine and from taking the contraceptive pill. They suggest that the contraceptive pill is associated with different, less deadly clotting conditions, therefore there is a risk of comparing apples with oranges. This is a fair point, however we still offer this perspective as the message we want to communicate is how this fear is related more to a fear of the vaccine, rather than fear of the illness itself. Millions of women every day willingly take the contraceptive pill, aware of the possible risks: these risks are well known and remain reasonably high, independent of the risk from the AstraZeneca vaccine.

One has to wonder why the US, Germany and Denmark suspended distribution of the vaccine, since the odds are so low (the US suspended Johnson & Johnson’s for three weeks, but the New York Times announced that the shots should be available again by the last week of April). Have governments become alarmists? Conditional probability comes into play here, which allows us to answer the real question: are these percentages the same for everyone, or are some categories more at risk than others? In other words, is the probability of venous thrombosis occurring 4 in 1,000,000 for anyone, regardless of any other characteristic (e.g., age, or gender), or does it perhaps specifically affect male professors over-50 called Nick? The editor hopes not!

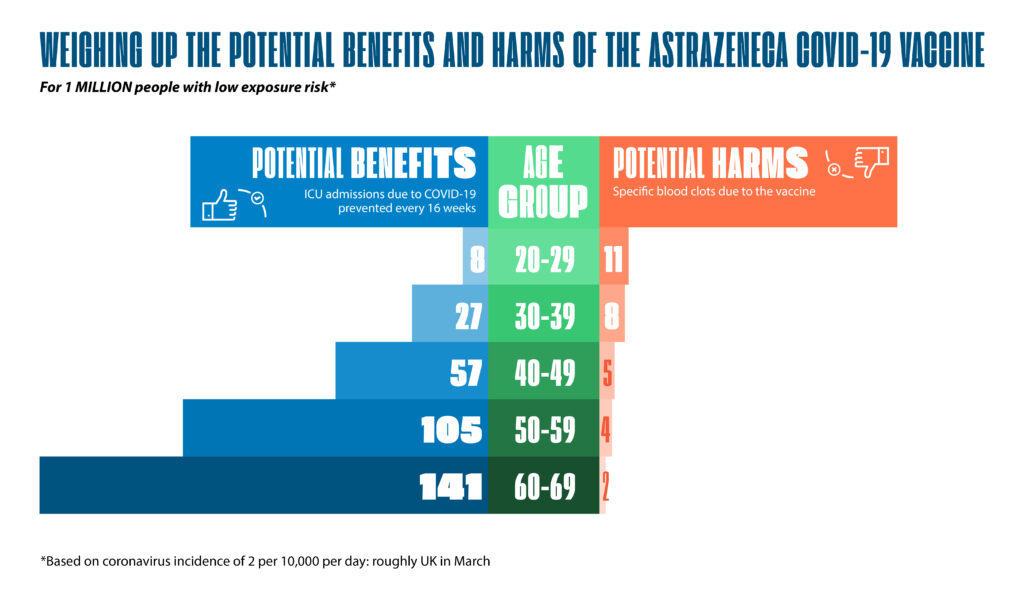

To say that there are 4 in 1,000,000 cases of thrombosis from the AstraZeneca vaccine is correct, but this does not take into account that the risk is unevenly distributed across the population. It appears, for example, that women under 60 are at higher risk of developing blood clots. Research from Cambridge weighed the risks and benefits and drew some interesting conclusions. At “low risk of exposure to Covid” (infection rates of 2 people per 10,000), which excludes higher risk rates due to prior illness or from higher exposure to the virus (e.g. during the first wave in April 2020 in the UK, when far more people were admitted to intensive care because they didn’t yet know how to treat the disease) the benefits of the vaccine seem to outweigh those of thrombosis risk.

In my age group, 30-39, for example, the vaccine prevents 27 out of 1,000,000 people from being admitted to ICU every 16 weeks (assuming 80% vaccine efficacy). At the same time, about 8 in 1,000,000 are at risk of developing blood clots. Risk and benefit estimates are based on actual cases reported up to March 31 and April 3, 2021, respectively.

The cost-benefit analysis helps explain why the European Medical Agency said that the benefits of the vaccine continue to outweigh the risks. In addition, the margin of benefit increases as age increases. For the 60-69 age group, the vaccine keeps 141 people per 1,000,000 out of intensive care, while it causes blood clots in only 2. This means that more or less anyone over the age of 30, excluding those at other risk of thrombosis or with previous illnesses, is better off getting either of these vaccines. What if Covid were a little more aggressive, with 6 cases per 10000 people, as in the UK at the peak of their second wave? The numbers in favor of the vaccine become even more overwhelming, for all age groups, including now the under-30s.

So, is it worth getting vaccinated? It depends on your interpretation of “worth it”. It is worth getting the vaccine in the sense that at the moment the numbers indicate we have more chance of becoming seriously ill with Covid than having a venous thrombosis from the AstraZeneca vaccine. Last but not least, these numbers are calculated based on the UK, a high population, high risk country. Such “worth” might be different for a remote population living in Tasmania.

With the vaccine roll-out, the line between political and scientific issues seems to be more difficult to define, and each country now decides for itself what the “science” is that it will follow. Even harder is tracing the role of propaganda and media in communicating numbers and facts. However, in order to avoid downplaying the risk, it remains important to reiterate that AstraZeneca was the subject of an investigation by the EMA, which declared thrombosis a rare side effect for women under 60 years old. But also, the EMA reaffirmed that the overall benefits of the vaccine continue to outweigh the risks in people who get vaccinated, and independent data seems to confirm this. After all, if we don’t vaccinate we give the virus more time and thus a better chance to mutate (reducing transmission also reduces the opportunities for mutation) and we allow it to continue to hold us in check for a good while longer.

Over The Pop

NUTS | Presented at the Sundance Film Festival in 2016, this documentary by independent filmmaker Penny Lane is about Dr. J.R. Brinkley, 1930s influencer, info-publishing pioneer, cynic salesman and inventor of what was for a while considered the solution to the King of Problems. The question the director asks us is simple: why do we refuse to see reality and believe what we like to believe? One to watch!

UNDER THE SUN | Nothing shows how reality is easily fabricated like the documentary by Vitaly Mansky, who was invited to North Korea to shoot a propaganda documentary. At the end of each day, unwanted footage was deleted by the Koreans, but Mansky kept backup copies and used these clips to assemble the documentary of the documentary. The film allows us a peek into the production of North Korean propaganda.

This article appeared for the first time on our fortnightly newsletter. To keep up with the scientific debate, join the community of Monnalisa Bytes and to receive a preview of all our newsletters subscribe here!

This article appeared for the first time on our fortnightly newsletter. To keep up with the scientific debate, join the community of Monnalisa Bytes and to receive a preview of all our newsletters subscribe here!